Lee's Lieutenants, A Study in Command

Vol. 3, Gettysburg to Appomattox

Charles Scribner's Sons, N.Y., 1944

Chapters IV

Historian

Account

Douglas Southall Freeman won the 1934 Pulitzer Prize for

biography for his volumes on Robert E. Lee. He followed this with

publication of this three volume work, on the command operations and narrative

history of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. This amounts to the seminal

work on this topic, the product of research "[begun] thirty years ago"

[from the jacket notes]. The importance he placed on this subject by devoting a

chapter to it is noteworthy as a scholarly argument to its significance.

"The Price of 125 Wagons" is Dr. Freeman's chapter title.

|

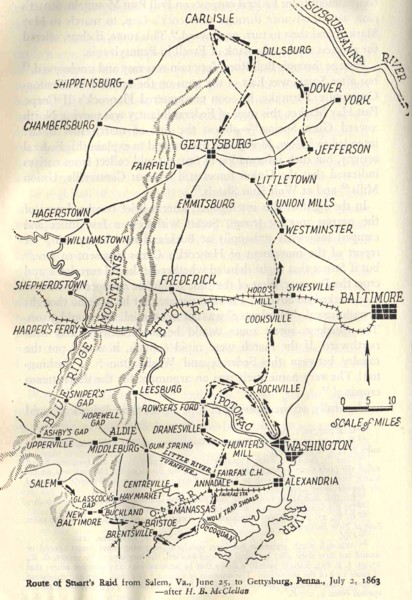

The issue is the importance of JEB Stuart's detachment from Lee's main army, along with most of the Confederate cavalry, in the run up to the Battle of Gettysburg and therefore the outcome of the campaign. The absence of cavalry performing their common scouting duties as the Confederate army moved into unfamiliar northern territory led to decisive lack of intelligence that shaped and triggered events. On a strategic level, poor intelligence meant that the Confederate army became heavily committed before they knew what they were facing at Gettysburg. With fuller intelligence, Lee might never have chosen to pursue this battle or made different choices in how to wage it. Tactical effects are apparent too. On the first day of battle, primarily dismounted Union cavalry first obstructed advance on the town and fought a successful delaying action to preserve favorable terrain for the Union forces in this battle. Or, the major Confederate flank attack on the second day was delayed by poor reconnaissance of the local roads and the needed route to move troops into position without exposing their surprise plan. Unwittingly and just in time against the eventual advance, Federal commanders extended and reinforced this exposed flank, thereby foiling the attack. If the attack had been ready and launched earlier in the day, as intended, the critical Federal positions and reinforcements would not have been in place to repel the attack.

|

Not only hotheads, but also typically calm analytic contemporaries, thought JEB Stuart should have been court-martialed for his actions in the Gettysburg Campaign. When Lee's adjutant, Col. Charles Marshall, first drafted the official campaign report, he included the recommendation of such a court-martial. However, Lee personally deleted this recommendation for the final report release. Shortly, thereafter, Stuart was killed in action so the point became moot, except as a historical facet for scholars to argue. The connection of this story to Rockville is one of cause and effect. The cause was, that in Rockville, Stuart captured the Federal supply wagons and chose to absorb them into his advancing column. The effect was, this slowed his rate of travel significantly, resulting in his tardiness to rejoin and serve the Confederate army, missing most of the precursors and two days of the Battle of Gettysburg. If events started here had not cascaded, unfolding so, perhaps the pivotal Battle of Gettysburg would have had a different outcome or never occurred altogether. If so, the Confederate invasion of the north in 1863 would have had a different outcome and then perhaps the whole Civil War might have ended differently. And from that lies a tantalizing possible difference on all subsequent American history.

|

© 2006, Peerless Rockville Historic Preservation, Ltd.

|

Freeman, Douglas Southall Lee's Lieutenants, A Study in Command Vol. 3, Gettysburg to Appomattox Charles Scribner's Sons, N.Y., 1944 Chapters IV |

The Price of 125 Wagons

....

In this state of affairs, Lee's instructions of June 22 and 23 applied: "...take position on General Ewell's right, place yourself in communication with him," and again, "...after crossing the river you must move on and feel the right of Ewell's troops, collecting information, provisions, &c." Said Stuart afterwards when his adherence to these orders had been brought into question: "I realized the importance of joining our Army in Pennsylvania, and resumed the journey northward on [June] 28th."

The intention was undeniable. So were three obstacles. The first was lack of information of Ewell's position. .... All the Stuart could decide on the 28th, then, was to proceed in the direction of Hanover.

In making that movement, a second manifest obstacle to a swift march was the condition of men and mounts. They were worn and hungry by the time they entered the enemy's country and they must be subsisted on what could be collected. Some delay was certain to result from this.

The third obstacle to a prompt junction with Ewell began to develop almost the hour the cavalry reached Maryland. It was the familiar one, the delight of men in the most destructive foe of discipline--booty. On the canal, at first arrival, the cavalry had captured several passing boat. Two of these had been laden with whiskey, but this was destroyed before it could do any harm. After that, no prizes were found on the way to Rockville, which was reached shortly after noon. The people of the village were dressed in their Sunday best and were full of curiosity. Pupils of a girl's school were smiling and Southern in sympathy. After an exchange of amenities and the destruction of the telegraph, Stuart might have ordered the march resumed promptly, had not cavalrymen suddenly had the most lamentable good fortune that ever had fallen to their lot.

Rockville, as it chanced, was on the direct supply line between Washington and Hooker's Army. Up this road, toward Rockville, Stuart was informed, a Federal wagon train was moving. All the Confederates had to do was to wait. Before long, the mounted guards approached. They were almost at the town before they realized it was in hostile hands. Once the "butternuts" were seen, the Union guards wheeled their horses and galloped back to spread the alarm. When they reached the wagons, the drivers became excited, frantically turned their teams in the road and started at a fast trot for Washington. In the mad chase that followed, the Confederates reached the [wagons], destroyed many vehicles and brought back to Rockville 125 of them. Said Col. R.L.T. Beale: "The wagons were brand new, the mules fat and sleek and harness in use for the first time. Such a train we had never seen before and did not see again." Eagerly the men examined the contents of the vehicles. Most of the loads were oats and corn, welcome enough to the hungry cavalry horses. In other wagons were bread, crackers, bacon, sugar, hams and a considerable volume of bottled whiskey. Singularly little of this ever reached the quartermasters. This wagon train was "Jeb's" stumbling-block. The length of the road and the weariness of his men might be surmounted by cheer and resolution; but a captured train of "125 best United States model wagons and splendid teams with gay caparisons"--this must be brought back to Virginia, no matter where, meantime, it had to be carried.

Stuart professed subsequently in his report that he considered an advance on Washington and abstainted solely because of the time required for such a move. He must have written this for hostile consumption, but at the time he determined, as a minimum next exploit, to cut the enemy's second line of supply, that of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. with good luck this would not be difficult. From Rockville the distance northward to the railroad, which ran on a wide arc, was about twenty-five miles and in the direction of Stuart's advance toward Hanover.

Unhappily if inevitably, [a brigade of Stuart's force] had become scattered in their pursuit of the wagon train. They and the other Brigades had accumulated about 400 prisoners. Much time was lost in starting the captured wagons on the road, in collecting the far-spread detachments, and in deciding what to do with the prisoners. Most of them were paroled at Rockville, but it was tedious business to write paroles for so many and to procure the signatures. Even when the prisoners were reduced in number, they encumbered advance.

Early on the of the 29th, after a night march of about twenty miles, the van encountered at Cookesville, three miles South of the railroad, a small Federal command. To scatter this was easy, but additional prisoners proved a nuisance. Although the guards and teamsters brought from Rockville were released, the new captives slowed movement. ....

....

.... For his own part, Stuart would have been hurt and ashamed had he known how anxiously Lee was inquiring for news of him and how faltering was the movement of the Army in the absence of cavalry. Ignorant of his chief's distress, Stuart was not concerned that day, apparently, because of his wagon train. It lengthened his column and placed his rearguard dangerously far from his van, but the long halt at Hood's Mill had allowed ample time for the wagons to reach Westminster. During the night, scouts brought word that the enemy's cavalry was at Littletown, six miles to the Northwest of Union Nills and across the line in Pennsylvania. If this intelligence caused Stuart to ask whether he should not burn his captured wagons, now that the enemy was at thand, the records give no hint. Said Major McClellan afterwards, "it was not in Stuart's nature to abandon an attempt until it had been proven to be beyond his powers...."

[A large Union cavalry force was encountered in Hanover when Stuart's forces arrived. The Union troops charged and had some initial success in dispersing the opposed Confederate troopers.]

.... [Not until Stuart] brought some of his field guns into play [did he know] his command was safe. He easily discouraged any further advance by the enemy, but his men were so scattered and his column so extended that he could not strike a counter-blow immediately. Had it not been for those captured wagons, all three of the Brigades would have been together and could have ended the action quickly. A lesser encumbrance were the prisoners who, surprisingly, now numbered 400--as many as had been paroled at Rockville and Cooksville. Hampered as he was by his train, Stuart could not bring himself to abandon it. He believed he was not far from the protection of the Confederate infantry, and, he later explained, he reasoned that if he parked the wagons temporarily and them made a detour during the night, he might bring the vehicles to his chief for use in collecting provisions from rich Pennsylvania.

.... After the enemy was dislodged from the streets of Hanover and was driven westward, the Confederate column began another of its deadly night marches. Said Stuart afterwards: "Whole regiments slept in the saddle, their faithful animals keeping the road unguided." Now and again some boy, nodding to one side, fell from his saddle with a thud but his comrades were too benumbed to laugh.

Such was the night of June 30 for "Jeb" Stuart, third of the men whose state of mind was making history for America while the Confederate Army converged on Gettysburg. He had gone on and on in the exercise of the discretion Lee had given. Almost six days Stuart had been on his raid. Not a single time had he heard from any of the infantry commanders with whom he was directed to cooperate. One dispatch only had he sent, and that on the 25th. Other adventure was to be his, but nothing he had achieved and nothing he could hope to accomplish with his exhausted men could offset the harm which the events of the coming days were to show he already had done his chief and his cause.