Season of Fire, The Confederate

Strike on Washington

Rockbridge, Pub. Co., Berryville, VA, 1994

Chapters XI - XIV.

Regional Historian

Account

An explanation of Early's 1864 Raid on Washington by regional author Joseph Judge.

[Note: This work is written in a journal

style chronicling events occuring at specific dates and location. Thus,

excerpts here appear as dated blocks of text.]

|

Judge, Joseph H. Season of Fire, The Confederate Strike on Washington Rockbridge, Pub. Co., Berryville, VA, 1994 Chapters XI - XIV. |

Confederate March on Washington and Attack

July 10 -- Road to Rockville

The [Confederate troops] who made that march [from Monocacy to Washington outskirts] remembered it all of their lives. Many of them had walked half way around the world behind a mule and a plow, breaking and riding over great morsels of red clay, and many had walked long miles to find a place where deer would, maybe, be found in the fall, but this march was an endless treadmill in a brown, gritty, cloud, where the dust clotted bloody wounds and the throat hawked up goblets of dark spittle and each crease of skin was sanded raw.

[Sgt. John] Worsham [Co. F, 21st Virginia Infantry] remembered that day as "terribly hot, and the men straggled a great deal" even though word swept the column that Yankee cavalry from Harpers Ferry was right behind them, sweeping up stragglers. ....

The sun reached ever higher in the hot July sky and the humidity seemed to clot the brown air as the columns went on, over hill and dale. [Gen. John] McClausland's troopers led the way, their mounts walking head down with flagging tongues, through roadside hamlets like Urbana and Hyattstown and Clarksburg, on elevated Parr's Ridge....

The Washington road sounded like an important thoroughfare, and it was, historically, being one of the earliest roads in Maryland, linking Frederick and Cumberland valleys with the Tidewater at the Potomac. but in reality, it was a narrow dirt pathway about eight feet wide that wound through farmland, past humble cabins and houses whose front porches were only four of five feet from the road. It was a land of small farmers and scattered slaves. Of the 18,322 people who lived in Montgomery County in 1860, seven thousand were black. Of that number, fifteen hundred were free.... The 5,421 slaves were scattered amoung many small farms; only one in every five farmers owned more than ten slaves.

It was favored country they were marching through, even though they could not see much of it through the dust and sweat. The settlers called it sugarland because of the maples. Drained by big creeks like Bennett's and Seneca, rolling pastures swept past islands of oak and beech, and stout brick farmhouses with wooden porches peered over fields of corn.

Between the America those scenes represented and the America that would emerge from this war would be the real rip in American history. The little places they passed through had grown around grants of land from an English king to a favored subject. Colonial life depended upon rolling the tobacco in huge hogsheads down to market, and moving the produce by wagon to feed the upstart towns like Georgetown and Montgomery Court House [Rockville].

The bottom line was that the economy was built on one person enslaving another. It was the Banquo's ghost at Philadelphia in 1776, this question of one person enslaving another because the welfare of the majority demanded it. It was the great debate that never took place. It was the language written by [Thomas] Jefferson for the Declaration of Independence, charging the English king with responsibility for this odious system--language struck out of that document at the insistence of the southern colonies.

The colonial fabric woven in 1776 ripped apart in 1860 because it had that terrible weakness in it from the beginning, and no one was willing to do anything about it. Once the question came down, it had to be faced; our civil war became institutional, motivated not by the American but by the Industrial revolution; the fatigued men who marched up and down the dusty roads of the 1860s were more spiritual kin to the doughboys of 1918 than the rebels of 1776.

So here they were, exhausted, choking on the dust of little places named Urbana and Hyattstown and Clarksburg, shuffling along on the hinge of history.

July 10, Late Morning -- Rockville Pike

Between Rockville and Washington lay a rolling countryside of large farms and plantations with fenced fields and pastures, a pretty and rich country. About halfway between the towns a landmark stood on a high hill on the west side of the pike, a white wooden church with four square columns and gothic windows whose red, blue and yellow panes glinted in the sun. Rebuilt in 1850 on the foundations of an 1820 church that had burned, the church served a Presbyterian congregation organized in the previous century. This Bethesda Meeting House would give its name in 1871 to the community that was growing even then around the Darcy Store post office. Its other, even older name, Capt. John's Meeting House, woudl also survive in corrupted form in the familiar local place name, Cabin John. The church included a slave gallery over the sanctuary.

Virginia Campbell Moore and her father were attending services in the stuffy church on this warm Sunday morning when a federal officer burst through the door. "The Rebels are coming! Get these horses away from here! Get to your homes!"

The Moores hastened to their home across the pike, climbed down into the cellar and closed the door over them. From the suddenly quiet road at the foot of their steep drive, they could hear an occasional horseman pass, but it was not until late in the afternoon that they harkened to distant booming from the west, exactly the sound of an approaching July thunderstorm [distant canon fire].

July 10 -- Gaithersburg

John T. DeSellum's Summit Hall farm stood just south of the village of Gaithersburg, right on the road to Washington. The fine federal house, built of weatherboard on log, reposed on a hill five hundred feet above sea level, skirted by fifty-eight acres of fenced pastures and yards and lawns on every side. It was part of a three-hundred-acre parcel owned by DeSellum, a substantial bachelor on the board of the Gaithersburg Milling and Manufacturing Company, a trustee of the Presbyterian Church, and a man of opinion with a controversial political history.

The Democrats of Montgomery County, led by George Peter, William Viers Bouic and William Brewer, wanted out of the Union. The county newspaper, Mathew Field's Sentinel, supported that view. At the war's beginning, many men had slipped south to ride with fellow countian Ridgely Brown or with Col Elijah Views White of Poolesville, who formed the 35th Battalion of Virginia Cavalry, of which Co. B "Chiswell's Exile Band" under Capt. George Chiswell, was made up of men from Montgomery [County, Maryland].

There was a pro-union party, the Whigs. Prominent among them were Allen Bowie Davis and Richard Johns Bowie and DeSellum, who had already suffered for his beliefs. When the military draft was instituted in 1862, DeSellum, as a prominent citizen of Gaithersburg, reported that he was "earnestly requested to draw the names. I replied it would be putting my character, property and like in imminent danger. But the Country demanded personal sacrifices.... I drew the names from the box.... My stockyard was burned and I was ostracized from Society."

DeSellum left an odd memoir of the war years, including the events of July 10. He recalls that after the sound of firing to the west on Saturday and again on Sunday morning, "for hours an ominous silence prevailed in the afternoon.' During these hot hours, a squadron of union cavalry under Maj. William Fry had appeared on the Washington road and deployed briefly on DeSellum's farm, with a skirmish line starting back west, in the village of Gaithersburg.

In Washington, Fry, of the 16th Pennsylvania, had been ordered to pull together a command from the troops at Giesboro Depot as quickly as he could. by Saturday night, as the corpse of Billy Scott was being carted up the hill toward Rose of Lima, Fry had thrown together five hundred mounted men and was on the way to reconnoiter the country above Rockville. On Sunday morning he fell in with Levi Wells of the 8th Illinois coming out of the Clopper road to Gaithersburg. They felt strong enough together to move past Gaithersburg, where they soon greeted the van of McCausland with enough musket fire to give them pause. But only pause.

Fry withdrew through the village to the DeSellum farm and put up another skirmish line, which as quickly evaporated when the head of McCausland's column appeared through the trembling heat waves. Fry disappeared eastward; in his place came a Confederate officer who rode up to DeSellum's door and told him that [Confederate] Gen. Early would be dining there.

"General Early arrived," writes DeSellum, "and I tried to be polite while my sister superintended the preparations for supper." His sister was Sarah Ann, born in 1812. Like John, two years her elder, she would never marry, and, like John, Sarah Ann was a substantial spinster. She owned, when the place was bought out by a cousin Fulks in 1885, no less than four beds, two sofas, tables, twenty-two chairs, two stoves and sundry other material goods. They also owned slaves, even though the worldly estates of both bachelor brother and spinster sister went to the Union Theological Seminary in New York and the Princeton Theological Seminary in New Jersey.

DeSellum reported that "Early and staff sat down to the table. A conversation commenced about the war and its cause. They saw I was a slave holder, and my remarks about John Brown's raid suddenly cause a Colonel Lee to abruptly demand of me 'whether I was for coercing the south!' As I did not intend to lie or act the coward, my reply was 'I wanted the south whipped back under the Constitution, union, and government of the United States--with the rights and privileges she had before the war.' again abruptly, Lee in a rage told me, 'You are an abolitionist--it is no use to blame the devil and do the devil's work.' and was very insulting."

....

Now there rose from the table in the DeSellum's house a figure "with the dignity and politeness of a gentleman,... his polished manner... an indirect reproof for Lee's violation of common politeness in the presence of my sister."

That dignified character bringing politeness back to the DeSellum table, said the host, was "Arnold Elsey"--by which DeSellum must have meant Brig. Gen. Arnold J. Elsey, who was at that moment two hundred miles away in Richmond. Although DeSellum could not remember who was at his table during this most memorable meal, his memoir marks his own position on both sides of the question---a slave-holder four-square for the union.

Even as they spoke, the diners could hear the sound of looting outside as the farm was stripped for food and fodder; horses and cows, beef and dairy, disappeared; tons of hay and barrels of corn were loaded into wagons; fences were torn down for firewood. On the nearby farm of Ignatius Fulks, one thousand, eight hundred cavalrymen and their animals were camped with an equally destructive result.

DeSellum accosted Early. "Do you intend, sir, to give me up to be indiscriminately plundered?"

"It is plain where your sympathies lie," Early replied, "You cannot expect favor or protection." Sarah Ann had already decided that, and had sequestered $3,000 and some government bonds in a safe haven--under her skirt.

July 10, 4:00 P.M. -- Rockville

By late in the day, [Confederate Gen. John] McClausland had chased [Union Major William] Fry all the way to Rockville and down the Georgetown Road. Fry paused at a hill east of the little country seat and dashed off a note to [Gen. Augur]:

| Washington Road Two miles from Rockville July 10, 1864 -- 4 p.m. |

|

General: I have taken position and formed. My rear guard is fighting the enemy near Rockville. I have been joined by a squadron Eighth Illinois Cavalry and expect to be engaged in a few moments. I would respectfully suggest that the forst in the vicinity of Tennallytown be strongly guarded as the enemy's column is a mile long. |

|

| Very respectfully, Your obedient servant, Wm. H. Fry Major, Commanding |

|

The head of McCausland's column quickly brushed aside Fry's pickets in Rockville. He broke off the pursuit; as the main force came up they were directed to the open grounds to the east of town, where the county fairs were held in peaceful times. [Approximately the Richard Montgomery High School playing fields today. This was the original county fair grounds and location of the Union garrison encampment, called "Camp Lincoln" throughout the war.]

Rockville had been the seat of Montgomery County since its formation in 1776. Named at first Montgomery Court House, the settlement of seventeen houses became the little town of Rockville, [when the county was] named for [Richard Montgomery] the fallen hero of Quebec, in 1801, when eighty-five lots were laid out on six streets, they quickly filled up with people drawn to the court--judges and lawyers and lobbyists and services attending to their needs. Two lively hotels did a brisk business during court sessions, as did the livery stables. In 1860, a city ordinance declared that "no horse, hog, shoat, goose ... or goat shall be allowed to run loose ... under penalty of one dollar." By the time McCausland appeared, the streets ... were paved, and the Montgomery House and Washington hotels were competing with Kilgore's Oyster Saloon for the diner trade.

McCausland honored the Montgomery House with his patronage. he summoned the regimental band, which assembled in the street outside the hotel and played martial music to the delight of the citizens, many of whom, including the mayor and leading citizens like Allen Bouic, were known southern sympathizers. McCausland paid his bill in confederate money.

July 11, Early Morning -- The Old Georgetown Road

Old Jube [Gen. Jubal Early] had a choice. From Rockville he could follow the Frederick Road straight on through the hamlets of Montrose and Darcy Store (later called Bethesda) before crossing into the District of Columbia a mile west of the commanding height of Fort Reno at Tenallytown, beyond which lay Georgetown and Washington City. Or he could avoid that well guarded approach and take his army east, by way of New Cut Road, past Samuel Vier's grist and saw mill which stood on Rock Creek. That road joined the old Union turnpike at Leesborough [Wheaton], which continued south through Sligo Post Office [Silver Spring] to the northern corner of the District, where it became Washington's Seventh Street.

Early chose to do both, dispatching the faster moving McCausland to the south, down the Georgetown Pike toward Montrose, while he prepared to take the main force eastward. The marching orders put Rode's division in the van of the column, with Col. George Smith's cavalry (Imboden's brigade, the 18th, 23rd, and 62nd Virginians; he was ill with typhoid in Winchester) on the point. Then came artillery, Ramseur, more artillery, Gordon, the wagon train and provisions, with Echols bringing up the rear. In Rockville, the passing troops noticed that horses killed in the cavalry skirmishing still ay in the streets, bloating and stinking in the rising heat.

July 11, Morning -- Rockville Pike

Maj. Fry's provisionals, stung by the action in Rockville, had spent the night on a hill about a mile east of that town. Outnumbered and almost out of ammunition, they began an orderly withdrawal as McCausland came out toward them. They kept riders in front of him all the way to the Old Stone Tavern, near modern Bethesda, when [Col. Charles] Lowell appeared with his reinforcement and took command.

At the village of Montrose, with its school for black children and Mes. Ball's popular tavern, the pike intersected with the old Georgetown Road opened by Gen Braddock in 1755. That road branched to the south and paralleled the pike until they joined again at Darcey Store.

Wanting no surprises on his flank, McCausland dispatched a column to follow and clear the old road. As the riders followed the big bend in the road to the east, they passed a 500-acre farm owned by the widow Matilda Riley. Here the hungry and thirsty troopers stopped at a little brook to gather calamus roots. They were observed by a young girl from the loft of a cabin that stood nearby. It was not any cabin but actually the cabin. Uncle Tom's cabin.

A black male child named Josiah Henson, born in 1789 in Charles County, was sold at age ten to Adam Robb, a tavern keeper in Rockville. Young Josie, as he was called, had come to Montgomery County because his mother had been sold to George Riley, whose farm was east of town on the Old Georgetown Road. Robb later agreed to reunite the pair by selling Josie to Riley, whose son Isaac managed the labor. There the adult "Si" Henson, lived for 25 years and became an overseer. One fine day he went to Newport Mill (also known as Duvall's) on Rock Creek near the hamlet of Kensington and was so moved by the words of an itinerant preacher, John McKenney, that he determined to become a preacher himself. In 1825, Si was sent to Kentucky with Riley's brother who was emigrating there. From Kentucky he escaped to Canada and was later admitted to the Methodist Episcopal Church, as a minister. He lived to the age of 94 in Canada, operating a farm called Dawn, and a school for former slaves. He traveled to England, where he filled every hall in which he spoke and met Queen Victoria, who gave him a portrait of herself in a gold frame.

One of the people interested in Si Henson's story was a woman author who interviewed him in Boston. She produced a series of articles for the Washington National Era, which would later become a book. Her fictional Montgomery County characters became famous in the struggle against slavery: Topsy, Little Eva, Simon Legree.

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin, or Life Among the Lowly was translated into twenty languages and sold six million copies. Later, Si wrote his own book, Uncle Tom's Story of His Life, with vivid recollections of the days spent near old Rockville, which he knew as Montgomery Court House, and his trips to Georgetown and Washington.

Could the soldiers have known the history of the cabin they passed that day? And if they did, what might they have thought of it?

July 11, Morning -- The Road to Washington

Only a few hundred [Union troops] blocked [the Early's Confederate army's] path to immortal military glory, but as the hours and the miles dragged by--it was twenty miles from Gaithersburg to Fort Stevens, a dozen from Rockville--it became clear that the column, imprisoned in the mid-90s heat and dust of the march, was reaching a state of collapse. it began spewing bodies as exhausted men fell out.

Early described the day. "[It was] an exceedingly hot one and no air stirring. When marching, the men were enveloped in a suffocating cloud of dust and many of them fell by the way.... I pushed on as rapidly as possible..., [but later, with heat waves shimmering and men gasping,] it became necessary to slacken our pace."

Ramseur would later write to his wife that "the heat and the dust were so great that our men could not possibly march further." John Worsham, whose unit was with Gordon, said the entire division was stretched out so thin from straggling that it looked like a line of skirmishers.

[On July 11th, Early's army continued to stagger through the heat to south of Silver Spring were it encountered the fortified works of Fort Stevens, lightly manned. However, the exhausted Confederate army was in no condition to assault a fortified position and the day was growing late. So Early rested his troops, gathered the strung out remnants, and prepared for an assault the following day, on July 12th.

Meanwhile on the Union side ....]

July 11, 9:00 P.M. -- Fort Stevens

[Union Gen.] McCook reported on the pick-up defense forces. "At 9:00 pm Brig.-Gen. M.C. Meigs reported at Fort Stevens with about 1,500 quartermaster employees armed and equipped. They were at once ordered into position near Fort Slocum, placed on the right and left in rifle pits. At 10 pm, Col R. Butler Price reported with about 2,800 convalescents and men from hospitals, organized into a provisional brigade composed of men from nearly every regiment in the Army of the Potomac. They were ordered into position in the rear of Fort Slocum."

A soldier in Wright's corps observed that "there came out from Washington the most unique body of soldiers, if soldiers they could be called, ever seen during the war."

[This was the crisis time for the defense of the Union capital. Later that night, veteran troops from the Union VI Corps, hastily pulled from the entrenchments enclosing Richmond and hurried by steamship up the Chesapeake Bay and Potomac River to the wharves of the District and Georgetown, and then quick marched through the City, began arriving at Fort Stevens. ]

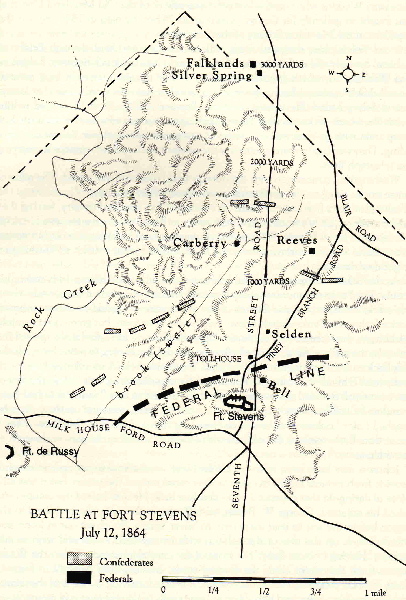

[July 12 -- Fort Stevens

By dawn this day, substantial Union reinforcements were in place in the relevant ring forts around Washington. Fort Stevens was competently manned for the force arrayed against it. Union forces also enjoyed the the benefits of a well fortified position and support of heavy artillery in the ring forts.

Alas,

a detailed description of the battle at Fort Stevens is beyond the scope of the

Civil War Comes to Rockville. The detail mentioned thus far is

offered as context for the campaign that passed to and fro through the

town. Suffice to say briefly here, Early did attack Fort Stevens on July

12th, (as portrayed by the map at right and contemporary image below)

but had scant success. By the close of the day, the Confederates deduced

the situation and stood in real danger of being overwhelmed in enemy territory

by counter-attack of a now superior concentration of Union troops. In the

fading light of day, Early's army made a good show of encamping in place showing

an intent to continue the battle the next day. However, this was a

ruse. Under cover of darkness, the army decamped entirely and started

marching in retreat, headed back to friendly territory in Virginia as quickly as

possible by way of fords of the Potomac River in upper Montgomery County.

In the Union lines on the morning of July 13th, Gen. Meigs,

commanding, reported "We remained in position until full daylight, and then

sent the men to their breakfast," then "completed our

entrenchments." They were fooled entirely by the Confederate ruse and

missed a prime opportunity to bag the whole of Early's army by counter-attack or

swift pursuit.]

Alas,

a detailed description of the battle at Fort Stevens is beyond the scope of the

Civil War Comes to Rockville. The detail mentioned thus far is

offered as context for the campaign that passed to and fro through the

town. Suffice to say briefly here, Early did attack Fort Stevens on July

12th, (as portrayed by the map at right and contemporary image below)

but had scant success. By the close of the day, the Confederates deduced

the situation and stood in real danger of being overwhelmed in enemy territory

by counter-attack of a now superior concentration of Union troops. In the

fading light of day, Early's army made a good show of encamping in place showing

an intent to continue the battle the next day. However, this was a

ruse. Under cover of darkness, the army decamped entirely and started

marching in retreat, headed back to friendly territory in Virginia as quickly as

possible by way of fords of the Potomac River in upper Montgomery County.

In the Union lines on the morning of July 13th, Gen. Meigs,

commanding, reported "We remained in position until full daylight, and then

sent the men to their breakfast," then "completed our

entrenchments." They were fooled entirely by the Confederate ruse and

missed a prime opportunity to bag the whole of Early's army by counter-attack or

swift pursuit.]

July 13, Morning -- Rockville

Col. Lowell's 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry had filed out from the defensive line at Fort Reno soon after sunrise and probed up the Rockville Pike until, around nine o'clock and a few miles below Rockville, it made contact with a Confederate force that had been withdrawing all that morning near Bethesda Church. The sparring began instantly. As Lowell came within half a mile of Rockville, he realized that Early's whole army had already passed by way of the old city road from Leesborough [Wheaton] and was heading out through Rockville toward Darnestown, Poolesville and the Potomoc River crossings.

Lowell's troopers moved in to harass and annoy Johnson's rear guard under Mudwall Jackson. As the riders in blue peppered the retreating column with fire from Spencer repeating rifles, Johnson found that matters were "getting disagreeable." he put in a squadron from the 1st Maryland under Capt. Wilson Cavey Nicholas and Lt. Thomas Green on a yelling charge along Commerce Lane [Montgomery Ave. today]. Many of the 2nd Massachusetts turned and bolted for the safety of the rear, but many others dismounted and, as Johnson recalled, "stuck to the houses and fences and poured in a galling fire. The dust was so thick that the men in their charge could not see the houses in front of them."

Nicholas and Green both were hit, their gunshot horses staggered and went down. Men in blue quickly surrounded them. Johnson, watching from farther west on Commerce Lane as his officers were seized, organized a second charge that drove Lowell backward along Montgomery Avenue and again filled the street with billowing dust, milling horsemen and blazing guns. James Hill of the 2nd Massachusetts, wounded and dismounted, ran to a nearby house [and collapsed in the yard of the Beall-Dawson House. He subsequently was taken in and cared for the the Beall sisters, and survived his wounds. Click here for story.]

In the melee, Green was taken back from his erstwhile captors, but Nicholas, the young inspector general of the Confederate Maryland line, had already been put on a horse and led from the field. As Johnson once again withdrew, Lowell followed, until the action spilled into the little valley of Watts Branch, where that stream crossed the Darnestown Road. Here Johnson's waiting picket line came under such galling fire from the Spencers that he again drove hard against Lowell, this time making him fall back all of the way through town and two miles down the Rockville Pike, where the 2nd Massachusetts pulled up, content to join forces with Fry's provisionals and the 8th Illinois Cavalry before resuming the chase.

Accounts of the action at Rockville note that "many men were killed," but realistic figures are impossible to come by. Certainly, Johnson thought himself "treated with more respect: as he continued down the road toward Poolesville, with sixty new prisoners in tow.

July 13, Noon -- Great Seneca Valley, Dawsonville

Beyond Rockville, the long [Confederate] column shuffled forward through the summer morning, the infantry swaying along in its loping stride with prisoners from Monocacy, creaking artillery and long lines of cattle and horses kicking up dust. As the miles went by, those able to find a stray horse to rest their legs did not hesitate to climb up, so much that Chaplain James B. Sheeran declared the column looked like "demoralized cavalry."

At midday, the long line of march had snaked its way down the broad valley of Great Seneca Creek between Darnestown and Dawsonville and, mercifully, a halt was declared. The men had been on the march since midnight, twelve hours before.

John Worsham, like many others, was "still barefooted; my feet were too sore to wear my boots." The scars would remain with him fir the rest of his life. Many of his comrades were "barefooted and footsore, and we had made a terrible campaign since we left our winter quarters." in the thirty-one days since they left Lee's army at Richmond, Worsham calculated, they had "marched 400 miles, fought several combats, and one battle, and threatened Washington, causing the biggest scare they ever had."

July 14, Morning -- White's Ford

Harper's Pictorial History of the Great

Rebellion displays a sketch [below] of the army crossing at White' Ford, and

it looks more like a scene from a Chisholm Trail cattle drive than from the

Civil War. in the foreground cattle are descending a slight slope and

wading into the shallow river, part of a long line that runs across to the

steeper hill on the Virginia side. Upstream is the wagon crossing.

Three wagons, drawn by teams of four horses, are in the river and seven are

preparing to enter it. Even farther upstream, a column of captured horses,

many but not most of them, with riders, makes an easier crossing. Somehow

the picture conveys a sense of relief. Said G. W. Nichols, "We were

glad to get back to Dixie land."

[Note, much of the mentioned commandeered or pillaged stock and supplies are

undoubtedly the farm bounty of Montgomery County getting carried away by the

Confederate army.]

[In later life, Jubal Early commented:]

In reply to those critics who wonder why he failed to take Washington, he said they should instead wonder "why I had the audacity to approach is as I did, with the small force under my command." He noted that the march of his corps in that summer of 1864 "is, for its length and rapidity, I believe, without parallel in this or any other modern war."